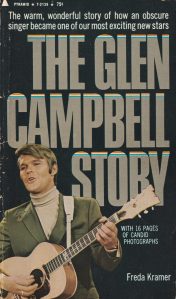

The Glen Campbell Story by Freda Kramer, Pyramid Books, 125pp, 1970

Rhinestone Cowboy: An Autobiography by Glen Campbell with Tom Carter, Villard Books, 253pp, 1994

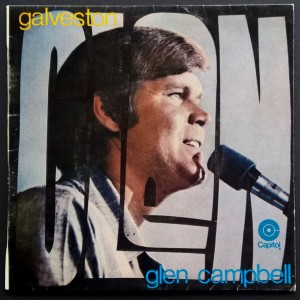

By the end of the 1960s, Glen Campbell was one of the biggest entertainment stars in the US. He’d already enjoyed huge success as a singer with US Top 10 hits in 1968 and 1969, and his easy-going personality had transferred readily to screens both big and small. After a well-received stint on The Summer Brothers Smothers Show, CBS had built a new TV variety show combining comedy and music around him which, after its premiere in January 1969, had become an instant hit. In June 1969, he had appeared in his first major feature film starring alongside John Wayne and Kim Darby in True Grit. Despite his inexperience as an actor Campbell never looks awed by his more famous co-star, and the film’s popularity has endured to this day.

The Glen Campbell Story, a mass-market paperback destined for the carousels of the nation’s supermarkets and railroad stations, explains how its subject had achieved such remarkable success. By any account, Campbell’s route to stardom epitomises the archetype of rags-to-riches. As presented in the book, his childhood growing up as the youngest of 12 children in the small town of Delight, Arkansas, is humble and character-forming, but for the most part happy. The Campbell parents, Wes and Carrie, have no choice but to send all their children out to work on their small piece of land, picking cotton, tending vegetables and looking after their pigs, cows and chickens. What the family lacks in material wealth, they make up for with the presence in their lives of music, “the heart, soul and core of life of the Campbell clan,” as the author puts it. The toddler Glen first hears music not in his own family’s church, the Church of Christ, but in local gospel churches, and with every member of his own family playing at least two instruments, he soon acquires a toy guitar made from an empty kerosene can strung with wire. His father gives him his first real guitar when Campbell is four, a three-quarter size model ordered from a mail order catalogue. He has no formal tuition in music, but his Uncle Boo, with whom he’ll spend many of his childhood and teenage years performing, shows him a few chords and by the time he’s seven, he’s singing and playing guitar with his brothers on a local radio show.

Determined to pursue his love of music, he quits school at 14 and heads to Houston where an older brother works, and after playing for a while with Uncle Boo he joins up with a band heading out on a tour of the South-West. The move proves to be a false start when he’s found to be too young for the venues they play and so Campbell has to head home, his first attempt at making his way as a musician ending in failure. With the help of another uncle in Alberqueque he makes a fresh start and forms his own band, Glen Campbell and The Western Wranglers, at the same time becoming a star on local TV and radio. He also gets married for the first time, to “the sparkling-eyed, vivacious” Diane Kirk, but his growing popularity and the couple’s decision to marry young bring an early end to their relationship. Three years later, he marries again to Billie Jean Nunley and the couple move to Hollywood where Glen hopes to further his career. He spends eight months touring with The Champs (of ‘Tequila’ fame), while also making demonstration records for other singers and – crucially – gaining a reputation as a session guitarist; one who doesn’t read music, but who can pick up a melody and song structure after hearing it once.

Campbell’s experiences in the studios of LA in the 1960s, playing as an often uncredited guitarist on sessions for, among others, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Nat King Cole, The Mamas and Papas and The Beach Boys (whom he joins for a period of four months in 1965 to cover touring duties from an indisposed Brian Wilson), coupled with his solid grounding as a dues-paying gigging musician, pave the way for his stardom in the second half of the decade. Although signed to Capitol Records from 1962, Campbell had felt his failure to break through to a wider audience stemmed from being paired with unsympathetic producers and unsuitable material. Kramer reports that Campbell even asked the label to tear up his contract, “before the company finally agreed to let Glen do the kind of music he wanted to do – and that’s when things really started popping!” Campbell duly finds and records ‘Gentle On My Mind’ and follows it up with ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’, giving audiences that first, magical taste of his interpretation of the words and music of Jimmy Webb. The rest, Kramer confirms, is country music history: “After nearly six years in the backyards of Hollywood, and seventeen years from the time he was flung off from Arkansas, he was the country’s newest ‘overnight’ sensation!” And so, to sate our fascination for the details of the lives of the rich and famous, we learn about Glen and Billie’s plans to build a huge new home overlooking Laurel Canyon, his devotion as a father to his children (“who respond to him like happy puppies”), his preference for country cooking “like possum stew, black-eyed peas and turnip greens” over fancier fare, as well as his modest consumption of alcohol (“he never drinks, except an occasional beer”). At the time of the book’s publication, Campbell had just completed his first lead role in the film Norwood, and his future plans include more work on his TV show, three albums, his own music publishing company, “and less concentration on concert tours, more on movies.” What, you might think, could possibly go wrong?

More than 20 years later, Campbell took to print to explain exactly what had gone wrong. If, like me, you come to Rhinestone Cowboy: An Autobiography, co-written with Tom Carter, immediately after reading The Glen Campbell Story, the effect is chastening, with many of the ‘facts’ in the earlier book crushed into the Arkansas dirt. The spine of the story is the same; Campbell’s life takes him from poverty to fabulous wealth and popularity as a result of his prodigious talent and devoted hard work. But where The Glen Campbell Story is a life made up of the snapshots in a photo album, much of Rhinestone Cowboy is a scrabble through a trashcan of painful memories. Campbell’s poor background was “merely existing”, he writes. “We didn’t just endure poverty, we wore it. You could see it in the distant, fearful stare of my parents.” His father’s main source of income is cotton, but however much the family pick, the money never lasts the year. His mother gives birth to each of the children at home, but within a few days of each new arrival she can be found working in the fields again. The relative who eventually helps him in Alberqueque had previously refused Campbell and his Uncle Boo the rail fare back to Delight after their first musical adventures on the road fall apart. “It would be a long time before I would forgive Uncle Dick for turning down relatives when they were in need,” Campbell writes, as if he still hasn’t managed to forget the slight. And that first romantic relationship forged in the early days of the singer’s popularity in Alberqueque? Campbell has to marry Diane because he gets her pregnant. He is 17, she is 15. Their baby is born prematurely and dies a few days later.

When the autobiography takes over from the period covered by The Glen Campbell Story, we find out that Norwood was not the start of a great career in the movies, but the end. Despite the involvement of many of the same team who had worked on True Grit – Charles Portis wrote the books on which the two films were based; both features were directed by Hal Wallis with Marguerite Roberts as screenwriter; and even Kim Darby, the real star of their earlier western, took a leading role with Campbell in the film – Norwood turns out to be a silly comedy that will soon date. “It was a ridiculous story that set back the cause of country music and perpetuated every stereotype of country musicians as hicks,” is Campbell’s verdict.

And that’s even before we get to the drink and drugs. His second wife introduces him to cocaine in the mid-1970s, and Campbell becomes a prodigious user. The drug, together with a consumption of booze that rates as rather more significant than just “the occasional beer”, dominates his third marriage and fuels flaring headlines in the early 1980s about his relationship with Tanya Tucker, then a rising country singer half his age with a taste for the party life and a ferocious temper to match. The sections devoted to their relationship make for painful reading, with neither side coming out of the account well.

Campbell knew that co-authoring a book like Rhinestone Cowboy was an act of bravery. By the time of its publication, he had renewed his religious faith, but the sense remains that in the act of revealing so much of his own behaviour Campbell was still seeking forgiveness. The sadness of both the autobiography and the earlier PR exercise is that neither really does his achievements justice. His skills as a guitarist, for example, are clearly down to hard work and an innate musicality, but in the books it seems almost as if he acquires his abilities in the same way that, as a child, he had learned how to pick cotton or skin a possum for the cooking pot.

The lasting beauty of Glen Campbell’s music lies somewhere beyond these pages. You won’t find it the press cuttings of The Glen Campbell Story or in the unblinking confessions of Rhinestone Cowboy. It’s caught up instead in the contradictions that dominated his life: the country singer finding acceptance in the pop world, the Republican who proves to be the single greatest interpreter of the works of a young Democrat, the young man who, but for his prodigious musical talents, could have seen out his days as a farmhand, and who spends much of his adult life wealthy and adored but adrift in the city. “Country boy,” he sings in the song of the name released as a follow-up to ‘Rhinestone Cowboy’, “you got your feet in LA but your mind’s on Tennessee.”

Campbell’s is a life that deserves a richer, more nuanced account, with a kinder eye for the personal foibles and a greater sensitivity to the music. Let’s hope that one day, we have the opportunity to read it.