Musician at Large by Steve Race, Eyre Methuen, 224pp, 1979

Musician at Large by Steve Race, Eyre Methuen, 224pp, 1979

The King’s Singers: A Self-Portrait by Nigel Perrin et al, Robson Books, 160pp, 1980

This post brings together two books by people whose faces are printed on my memory from appearances on TV during my childhood. When I was growing up I couldn’t have told you with complete confidence exactly who these individuals were or what they did, other than that they were a visible part of the vast, mysterious world of musical entertainment. But as it turns out, both acts had interesting bit parts to play in the history of rock and pop.

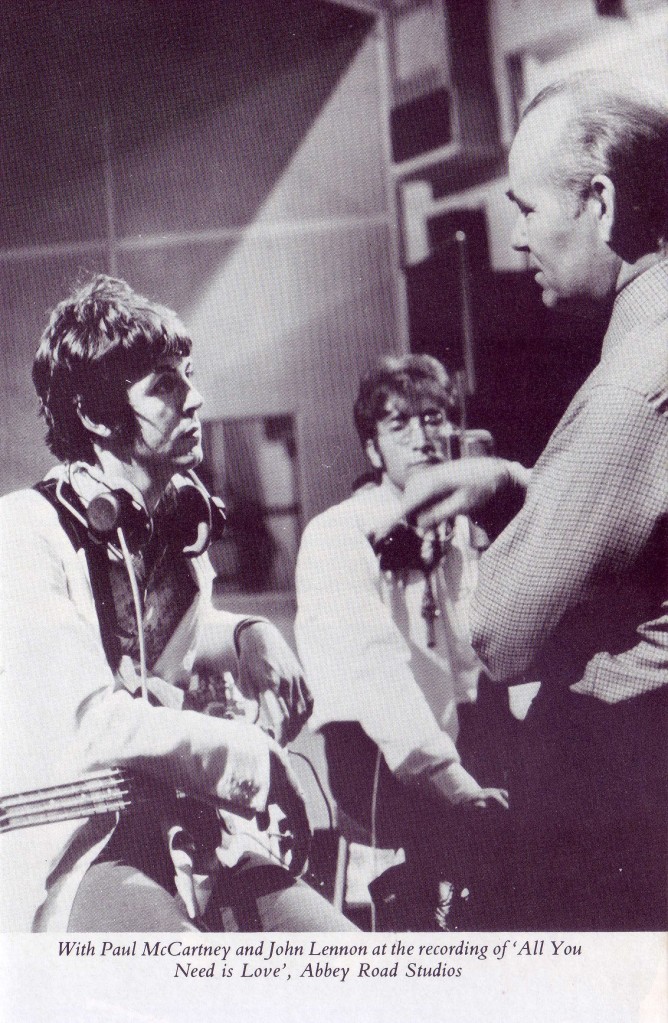

Steve Race was a presenter on the BBC radio and TV series My Music, in which a panel of amiable regulars joshed and performed their way through musical challenges set by Race. His autobiography Musician At Large details what could have been several lifetimes in music, given that he was also a journalist, a composer of both serious music and advertising jingles, an arranger and accompanist. I bought the book on the strength of a photo it includes showing Race chatting to Lennon and McCartney. The occasion was the 1967 TV one-off Our World in which he introduced the Beatles appearing to record, and then playing in full, ‘All You Need is Love’.

Race describes a quiet childhood growing up in 1920s Lincolnshire which, with its emphasis on regular attendance at the local Methodist church, seems about as far removed as possible from the cosmopolitan world of jazz clubs and broadcasting studios he would later know. He realised as a child he could improvise easily at the piano, and later considered this ability in other young performers to be a sign of “true musicality”. As a student at the Royal Academy of Music his piano teacher makes him aware that “music is a profession as a well as a calling”, and his understanding of this is borne out by the many roles in music he went on to enjoy. Although perhaps ‘enjoy’ is the wrong word, since what also comes through is how fed up Race eventually becomes with different parts of his working life. In the space of two pages he recounts firstly leaving his place in Cyril Stapleton’s band (“after three months of playing all night and arranging all day”), and then the experience of a particularly tough engagement which leads him to decide he will no longer play at dance parties (“at seven in the morning I was decanted on to my Wembley doorstep with a temperature of 103.”). Later on in the mid-sixties, after a busy few years playing and reporting on the subject, he becomes “disenchanted with jazz, almost bored by it”, blaming a “surfeit of live performances in clubs and concerts” and the endless soloing jazz performers indulge in. Even though at the end of his story Race writes that he is contented in retirement, there’s something a little sad about this. The music simply seems to have worn him out.

Curiously, and despite the inclusion of the Lennon and McCartney picture, Race has nothing to say about his part in Our World. Also absent are any detailed thoughts about pop music more generally, which is odd given that while working as a journalist at Melody Maker in the 1950s he was fiercely critical of early rock’n’roll. But by the time he recorded his own LP Late Race in 1965, his attitudes had at least softened enough to include covers of ‘All My Loving’ and ‘Till There was You’, and to state simply in the album’s sleevenotes that “John and Paul write great tunes.”

The King’s Singers gave their first performance in 1968 and are still going today (with different members) as a vocal harmony group, the ‘King’ of their name referring to King’s College, Cambridge where a group of six choral scholars formed the act. Pictures of their line-up from the mid-1970s will be familiar to many, even if you don’t know the names of the singers themselves. The group was often to be seen on TV light entertainment programmes, decked out in matching suits and velvet dickie bows and singing anything from madrigals to recent chart hits, all impeccably arranged and performed. If your musical tastes veer into the wilder fringes of easy listening, you may know their versions of ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.

Given that an early incarnation of the band called themselves ‘Scola Cantorum Pro Musica Profana in Cantabridgiense’ and performed at a festival of church music in rural Wiltshire, I wasn’t expecting too much in the way of rock’n’roll from the band. And yet in their own quiet, self-deprecating way, the King’s Singers’ connections to pop music culture extend beyond their song choices. They made a total of three albums with George Martin, and also had a significant working relationship with Greg Lake of Emerson, Lake and Palmer. It was Lake who recorded and arranged their version of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, a song which the band put out as a single in 1978. The picture cover for the release, which featured a scratch’n’sniff strawberry-scented sticker, was – for the King’s Singers at least – staggering in its out-of-character sauciness. The band sang backing vocals on ‘Closer to Believing’ from ELP’s Works, Volume 1 and repeated the word ‘humbug’ for a song of the same name on the B-side of Lake’s ‘I Believe in Father Christmas’. Lake was such a fan that he wanted the band to accompany ELP on a tour, although that intriguing double-header never came about because the singers were committed elsewhere.

And if you want an unlikely tale of excess on the road, try this. The story begins at the end of a 1977 tour in Sweden where the group are invited to a student party; already, you feel, the kind of details which make for a decent rock escapade. Conscious of other engagements back in Britain the next day they plan to “just drop in for a brief cordial for the sake of appearances.” In fact, they leave at 5am the following morning, considerably the worse for schnapps, having also managed to lose one of their members along the way. During the night they discover that their hosts, generous with the measures and eager to hear them sing, have been testing their stamina: the locals were “determined to see if [the group] were made of the same stuff as Manhattan Transfer, whom they had entertained a couple of weeks previously and who had last been seen crawling into a sauna at 6.30 in the morning.”

Who knew that these titans of easy listening were such prodigious revellers? And that might be part of the problem with the critical reputation the band has often had: fruity record sleeves aside, little of this personality comes through in their endlessly polite, if highly accomplished, records and performances. In the book they bravely quote a reviewer from the Financial Times who wrote in 1976 that they have a “supreme ability to reduce all the music [they] sing to its lowest common denominator.” Steve Race, who was very much a fan and with whom they appeared on many episodes of the radio series Invitation to Music, also writes the foreword to the book, and states that “the breadth of their repertoire is a significant step towards the ‘one music’ so devoutly to be hoped for.” Enthusiasm for lots of different types of music is a great thing, but ‘one music’ suggests a levelling across many styles. Why would you want to lose all that grit, that singularity?

You guys! See also the post on the Association for more about bands fooling around on grass.

Neither of these books is an essential read, but to their credit neither yielded quite what I was expecting either. Anecdotes aside, the books convey very well the slog of the lives of professional musicians, with both acts revealed to be hugely hard-working. At one point the King’s Singers note that they record at least three albums a year, as well as giving countless TV and live performances, and Steve Race actually begins his book by recounting the pressures of work which led to a heart attack in 1965. No wonder he has so much to say about being fed up. If pop stars grumble about how tough their schedules are, they might also want to a spare a thought for their more serious counterparts.

To get a sense of what all this hard work created, click on the link below to hear the King’s Singers’ unique take on ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, and if you’re really keen, try and track down Steve Race’s inspired jazzy take on the theme from ‘Coronation Street’.

And if you ever find yourself stuck in a hotel bar at 3 in the morning with Manhattan Transfer, don’t say I didn’t warn you.