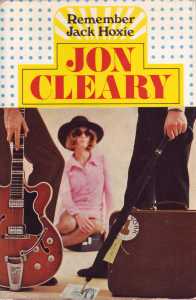

Remember Jack Hoxie by Jon Cleary, Collins, 320pp, 1969

Remember Jack Hoxie by Jon Cleary, Collins, 320pp, 1969

When the prolific novelist Jon Cleary died in 2010, the obituary which appeared for him in The Australian noted that the late writer’s literary hero had been Graham Greene. By a happy coincidence, Greene became Cleary’s editor when the Australian first moved to post-war England, and it was Greene who also made a helpful suggestion about what the young author might try his hand at next: “Write an entertainment,” he said, “because it will teach you about construction.”

Cleary went on to write many “entertainments”, including a series of crime novels featuring Sydney cop Scobie Malone. Remember Jack Hoxie was Cleary’s twenty-second published book, and although it came out in 1969, the novel appears to have existed in another form for some time prior to that. The title ‘I Remember Jack Hoxie’ was noted in the Hollywood trade press as early as August 1966, when Boxoffice magazine reported that a long short story of that name by the author had been purchased for production in 1967. Variety then reported at the time of the book’s publication that another company had recently bought the rights to the work. Sadly, the book was never turned into a film. With its story of a young British singer finding fame overnight, and the perspective on the pop scene offered by the father witnessing the chaos of fandom and his son’s burgeoning celebrity at first hand, a cinema version would surely have made an intriguing addition to the canon of 1960s films about the music business.

As this summary might suggest, one of the main aspects of Remember Jack Hoxie is the gap between the generations and of course, the world of pop music provides an excellent means of examining this. While the difference in ages between the singer, Bob Norval, who is in his late teens, and his widower father Patrick, 41, may not seem of particular consequence today, it was much more of an issue in the 1960s in terms of the outlook and aspirations of the two generations. Norval senior works as an insurance salesman for Rock of Ages (the company’s name doubtless a nod to the other type of rock in the book), who has taken the security of a mortgage, pension and guaranteed promotion over his original plan to teach history. “Ambition,” Cleary writes of Patrick, “disappeared like a lost file among the ledgers of Rock of Ages’ head office.”

His opportunity to be rescued from a life of suburban anonymity comes when Bob is picked up as a new talent by Aussie expat Brian Boru O’Brien, a young songwriter and the manager of the Southern Cross music agency, who suggests that Patrick should sign up too – not as a performer, but as a visible means of connecting the generations. This is how O’Brien explains his proposal to Patrick, who has just had his first eye-opening experience of a rowdy mob of his son’s young fans:

‘Everyone is always talking about the generation gap, but no one ever tries to do much about it. I won’t make you a swinging dad. Nobody will buy that, even the kids don’t like it. But you saw to-day how they rushed to get your picture – it’s a whole new gimmick. Father And Son Who Understand Each Other. The pop world of to-day and the swing world of yesterday.’

Despite some misgivings, Patrick signs on. As O’Brien’s language reveals in his explanation here – not “even” the kids will go for a swinging dad, but a “gimmick” could still be a winner – O’Brien has the pop manager’s typical interest in getting maximum value out of his acts and maintaining ‘The Image’, as it’s referred to repeatedly in the book, at all costs. But just as his acts rely on O’Brien’s continued support and enthusiasm, so O’Brien also has to rely on the talent of his arranger and songwriting partner Cham Hubbell. For all his abilities, Hubbell is an obnoxious individual and contemptuous of almost everyone around him. At the end of the book Hubbell stitches up the Norvals by planting drugs in Bob’s luggage on a flight back to Britain. But rather than risk the reputation of both his star and his business partner and the irreparable damage it would cause to The Image, O’Brien persuades Patrick to take the blame instead of Bob. Patrick actually goes to prison as the thankless consequence of his actions.

In another quote attributed to the author in the obituary referred to above, Cleary realised at the age of 40 that he didn’t have the “intellectual depth” to be the writer he might have wished to be, so instead decided to be “as good a craftsman” as he could. In its attention to period detail of the pop world, the book demonstrates strong evidence of Cleary’s thorough research. Bob starts out as a singer in a workaday outfit called The New Type, formed with his fellow students at the London School of Printing. O’Brien spots him at a very of-its-time gig at the Modern Art Institute in Bloomsbury which features psychedelic slides, a lightshow and, as the members of the band note in wonderment, ‘something called a Sensual Laboratory’. When Bob auditions for O’Brien, his songs include a couple of waltz ballads of the type then being made fashionable by Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck, a phenomenon of the time otherwise little remarked upon in fiction. Under the guidance of his managers and while on tour in America, Bob is presented for one night only and without success as a folk revivalist, and then as a soul singer, which he is only able to do with conviction once he has experienced personal trauma. While Cleary sometimes strains to educate his readers about the workings of the pop world, the book mostly benefits from the critical distance of the experienced author looking into this strange new world. It would be fascinating to know who exactly Cleary followed on tour or watched in the studio to inform his preparations for the book.

Towards the end of the novel, the pop background fades away and Cleary shows himself to be more interested in the relationships between his characters than the circumstances in which they find themselves living and working. O’Brien has mockingly referred to Patrick as ‘Dad’ throughout the book, but by the end, there’s a suggestion that Patrick has become a father-figure for the young pop manager. Norval father and son, facing the world together without wife and mother Brenda after her death from cancer, are able to build on their relationship through their shared experiences of the pop world. And the story concludes with Patrick starting a new life in Spain with O’Brien’s assistant, whom he has courted – the old-fashioned word seems appropriate here – throughout the book.

As well as its clear pointers to prevailing trends in pop music, Remember Jack Hoxie occupies a specific point in history. The morning after the disastrous gig where Bob has failed as a folk act, the touring party hears that Bobby Kennedy has been shot. This dates the scene to June 1968, and contemporary American politics more generally form an important part of the novel’s background. Patrick is several times described as looking like Ronald Reagan, the actor turned politician who at that time was the Governor of California, and Cleary extends this physical likeness by imbuing Norval with the sort of broad-shouldered sense of decency and virtue you would only associate with someone of a previous generation. Indeed, what brings the generations closer together in the book is Patrick’s kindness towards the young people around him on the tour. After Bob’s girlfriend Tina, a backing singer for the band, has an illegal abortion in Los Angeles, it is Patrick who finds the doctor responsible and gets Tina to hospital. Henry, the black singer with Bob’s support act, is set up upon by youths in Boston because of his colour, and while everyone around him in the all-white touring party tries their best to say and do the right thing, it’s Patrick who has the most meaningful conversation and connection with the teenager.

And Jack Hoxie? Well, I confess I hadn’t heard of him when I read the book and until I finished it and looked up the details, I wasn’t sure if he was another fictional creation. Hoxie was in fact a silent film actor best known for his roles in westerns, who had died only four years before Cleary’s novel was published. Patrick’s elderly next-door neighbour is said to have met him once and still holds him in high regard because he never let his fame go to his head. ‘Nice chap,’ says the neighbour of Hoxie. ‘Nothing like a big fillum star at all.’ Patrick remembers this, and in his escapades in the pop world he refers to the actor’s name as a means of keeping a sense of perspective. But there’s an ambiguity in the book’s title which betrays the fickleness of fame and the world of ‘The Image’ in which he and Bob have found themselves. What might be taken as a command, an instruction not to forget Jack Hoxie and all that he stood for, could also be read as a question asked half in doubt: remember Jack Hoxie? On the day his son headlines at the Hollywood Bowl, Patrick uses some free time to see what he can find out about the actor. But his search reveals little, and he discovers that not even the Screen Actors Guild has a file on him. As he realises soon enough, most people don’t remember him at all. And as a member of an older, wiser generation, Patrick is well able to make the connection between Hoxie, his own son, and Patrick’s brief moment in the world of pop stardom as the Father Who Understands.

Hello. I think he’s right. I don’t think the kids will go for a swinging dad at all. I read this. And it’s good. hx